Compare and Contrast Analysis Organization

We can call the two ways of organizing a compare and contrast block-by-block (or lumping) and point-by-point (or splitting).

Whether organizing by lumping or by splitting will depend largely on your purpose and on the complexity of the material. Lumping is often used for long, complex comparisons, if for no other reason than to avoid the ping-pong effect, but no hard-and-fast rule covers all cases here. When you offer an extended comparison, it is advisable to begin by indicating your focus, that is, by defining the main issue or problem and also by indicating what your principle of organization will be in the introduction.

The University of Toronto Writing Centre offers a helpful resource on the comparative essay.

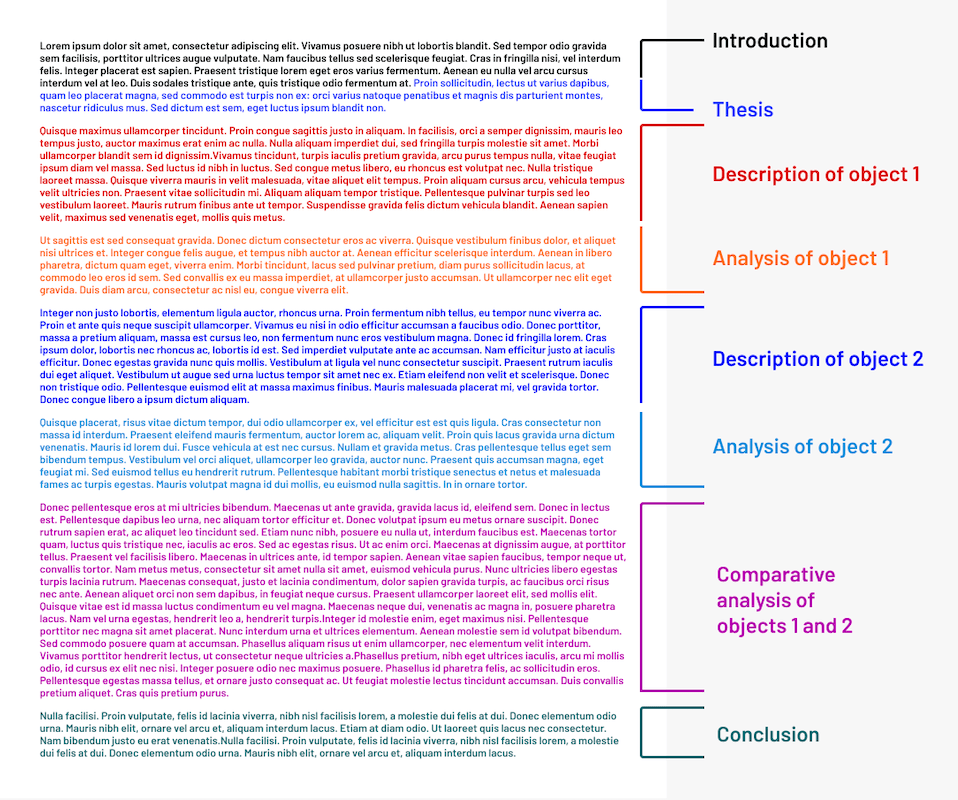

The “lumping” or “block” method:

After introducing the two works in the intro paragraph, write a full description and analysis of each work, separately.

After establishing the key traits and qualities of the two works (once the reader has a strong sense of what each work looks like and understands its formal qualities), bring both works together to compare the two examples.

Lumping

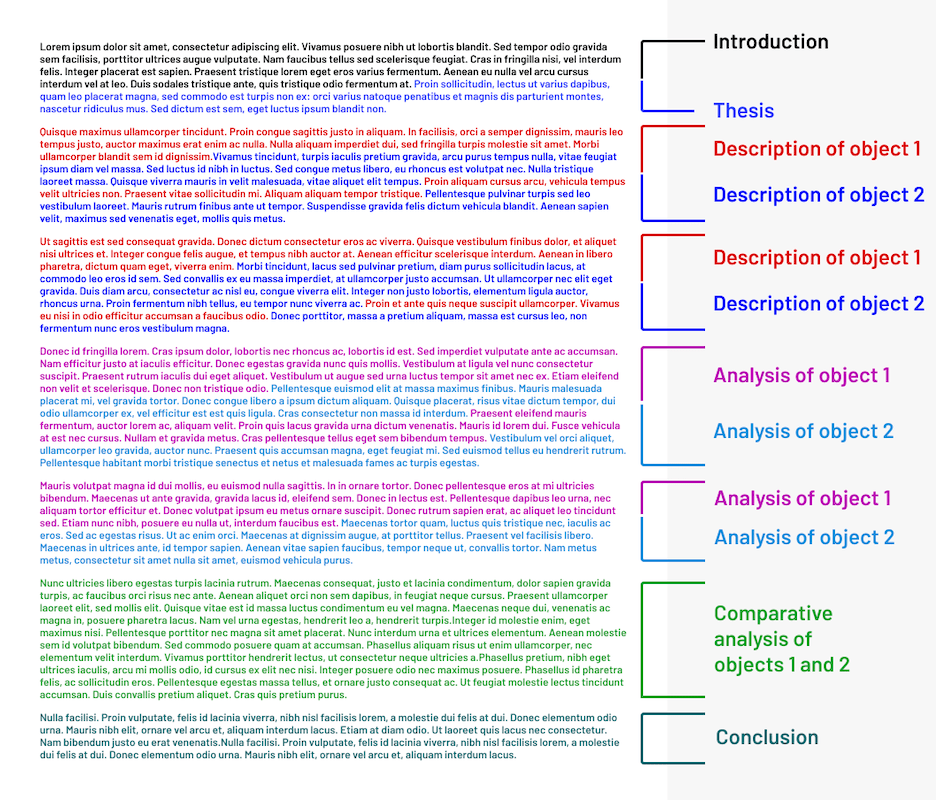

The “splitting” or “ping- pong” method:

After introducing the two works in the intro paragraph, describe and analyze the two works together. In this case, it’s best to organize paragraphs around certain topics (for example, the first descriptive paragraph can focus on certain formal elements, while the next paragraph can discuss specific design principles and stylistic effects)

After raising all the key points of similarity and difference between the works, summarize the key points of comparison you’ve analyzed.

Splitting

-

Block-by-Block (Lumping)

When you compare block-by-block, you say what you have to say about one artwork in a block or lump, and then you go on to discuss the second artwork, in another block or lump.

For example, a lumping structure would be as follows:

- Thesis about the Buddha and the bodhisattva

- The Buddha (posture, folds of garments, inner nature)

- The bodhisattva (posture, folds of garments, inner nature)

- The Buddha and the bodhisattva (synthesis)

If you lump, do not simply comment first on X and then on Y.

Let your reader know where you are going, probably by means of an introductory sentence.

Don't be afraid in the second half to remind the reader of the first half. It is legitimate, even desirable, to connect the second half of the comparison (chiefly concerned with Y) to the first half (chiefly concerned with X). Thus, you will probably say things like "Unlike X, Y show…" or "Although Y superficially resembles X in such-and-such, when looked at closely Y shows…" In short, a comparison organized by lumping will not break into two separate halves if the second half develops by reminding the reader how it differs from the first half.

-

Point-by-Point (Splitting)

When you compare point-by-point, however, you split up your discussion of each work, more or less interweaving your comments on the two things being compared, perhaps in alternating paragraphs, or even in alternating sentences.

For example, a splitting structure would be as follows:

- Thesis about the Buddha and the bodhisattva

- The Buddha (posture)

- The bodhisattva (posture)

- The Buddha (garments)

- The bodhisattva (garments)

- The Buddha and the bodhisattva (synthesis)

Splitting is well suited to short essays or for occasional use within longer essays, but if it is relentlessly used as the organizing principle of a longer essay, it is likely to produce a ping-pong effect. The essay may not come into focus—the reader may not grasp the point—until the writer stands back from the seven-layer cake and announces, in the concluding paragraph, that the odd layers taste better.

In your preparatory thinking, splitting probably will help you to get certain characteristics clear in your mind, but you must come to some conclusions about what these add up to before writing the final version. The final version should not duplicate the preliminary thought processes; rather, since the point of a comparison is to make a point, it should be organized so as to make the point clearly and effectively.

If you split, in rereading your draft:

- Ask yourself if your imagined reader can keep up with the back-and-forth movement. Make sure (perhaps by a summary sentence at the end) that the larger picture is not obscured by the zigzagging.

- Don't leave any loose ends. Make sure that if you call attention to points 1, 2, and 3 in X, you mention all of them (not just 1 and 2) in Y.