Creation of the Birds From Brenda J. Caro Cocotle, "Creación de las aves, 1957," in Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, edited by Caitlin Haskell and Tere Areq (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2023), 60–65.

Take some time to closely look at and analyze Remedios Varo's Creación de las aves (Creation of the Birds) painting. What details do you notice first and why? How did Varo use the elements of art and principles of design within the tapestry? After spending some time analyzing Creación de las aves (Creation of the Birds), read the following excerpt from Caitlin Haskell and Tere Areq, eds., Remedios Varo: Science Fictions (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2023).

Remedios Varo, Creación de las aves (Creation of the Birds), 1957. Oil on hardboard, 54 x 64 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

Remedios Varo's Creación de las aves (Creation of the Birds) holds an important place in the artist's body of work. Commissioned in 1957 by Manlio Hernández for his wife Ana María (an admirer of Varo's art), the painting has since enjoyed enthusiastic critical reception, as proven by the number of times it has been exhibited: thirty-four since its first presentation in 1958, including as recently as 2022, when it was featured in The Milk of Dreams, in the 59th Venice Biennale. It is difficult to pin down what has drawn audiences to this work over more than sixty years; perhaps it is the fantastical story or the vivid assemblage of fine details. Or perhaps it is the idea of an alternate world where the rules are different and the potential for the impossible is the norm.

Peering into an intimate room or tower, we witness a hybrid owl-human engaged in a task that at first looks like painting, but is in fact much more. Holding a red -tipped brush strung from an instrument hanging around their neck, the figure applies pigment to a support. This, however, is only half the technique; holding a prism in their other hand, they refract light from a faraway star onto a newly painted bird. Somehow, this combination breathes life into the image, which, now animated, lifts off the page and spreads its wings to join its avian companions rushing toward the window. The details—a painter's palette, a prism, a complex system of beakers and pipe stills, and a coffee roaster—evoke both a laboratory and a studio, yet the act of creation Varo depicted operates well beyond the laws of science or the rules of artful mimesis.

Many scholars, including Tere Arcq, Georgiana M. M. Colvile, Janet A. Kaplan, and Magnolia Rivera, have written about the symbolic elements and Varo's references in this painting. It is considered one of her most representative works and the one that best expresses her ideal union of art, nature, and science. Indeed, Varo depicted the moment of creation as a balancing act of forces: in nature (external material substance, starlight, primordial elements), art (executing hand, brush, pigments, subject matter), and science broadly defined (alchemy, instruments, vessels and pipe stills, the processes of change and decomposition). One concept in particular bridges the various currents of thought from which the artist drew and, at the same time, allows these mutually exclusive dimensions to coexist: transmutation.

A process that changes the essence of a material, transmutation is central to notions of alchemy, which involves separating the material and spiritual properties of elements to isolate the inherent physical properties capable of mutability. Unlike transformation, which implies the modification of an external form, transmutation describes a change to the internal structure. This theme also related to evolutionary biology, chemistry, and taxonomy appears again and again in Varo's works. Varo identified art—something capable of modifying the order of everyday life and introducing other systems of knowledge and perception—as a productive point of departure for engaging these scientific ideas.

Varo's choice of protagonist alludes to birds' symbolism of knowledge in various cultures and disciplines. The ancient Greeks, for example, practiced ornithomancy (called augury by the ancient Romans), interpreting the flight of birds as omens; Germanic tradition assigns these animals the role of messengers between the worlds of life and death; and alchemists developed a complex nomenclature in which each of the four stages of the quest for essential materials is represented by a type of bird: raven, peacock, swan, and phoenix. The owl has long been considered wise: the Greeks represented Athena, the goddess of wisdom, with one of these birds on her shoulder, and the white owl became the symbol of alchemists and, by extension, of chemists during the transition to the so-called modern era.

In these contexts, however, wisdom does not mean the accumulation of knowledge but rather the ability to see beyond the limits of what is evident—another point of connection with Varo's understanding of art. In Creación de las aves, Varo introduced play between the image and the object, appearances and the real. She perceived and created—that is, revealed—what is not there; she did not represent but rather transformed with her gaze and hand. The figure creating the birds oscillates among human being, alchemist, scientist, and demiurge; the creator uses vessels, pipe stills, and prisms to distill the elements around them into a source of primary colors, which form the base of every possible combination of color and imbue life with a spiritual force.

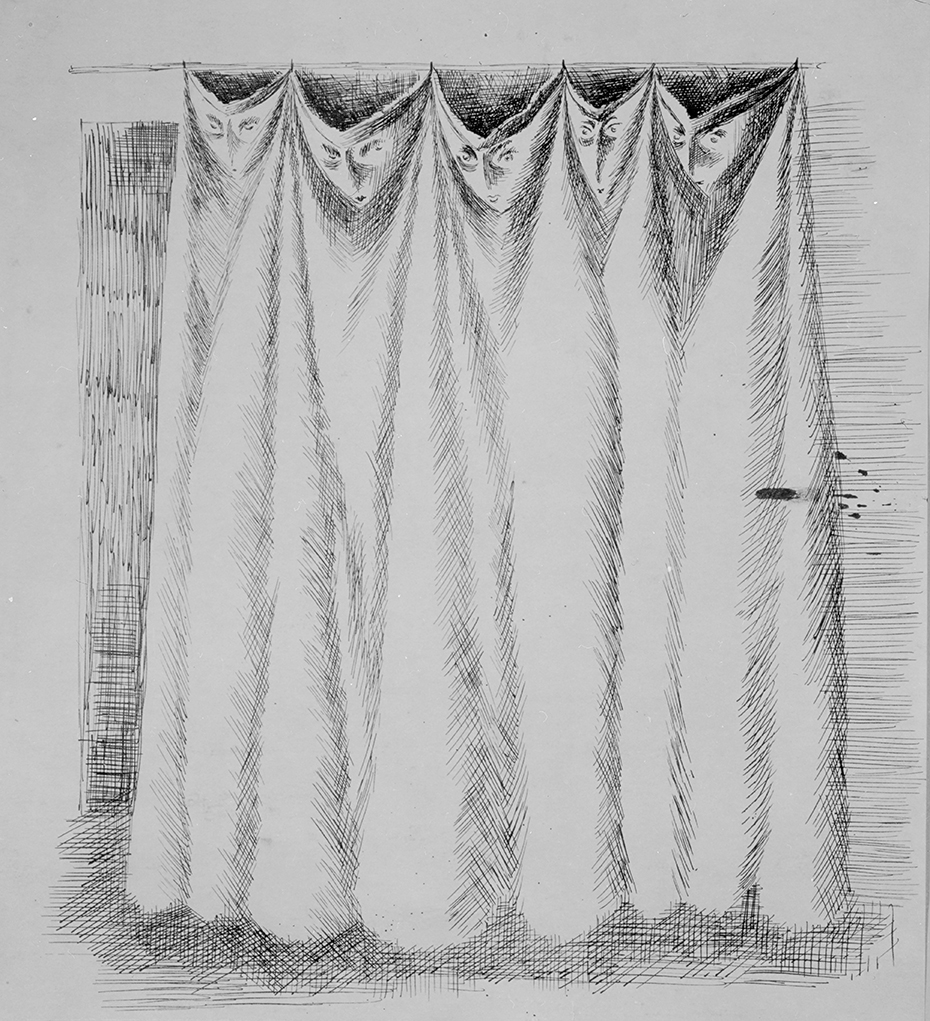

Remedios Varo, Cortina, o Visión (Curtain, or Vision), 1959. Graphite on paper, 28 x 26 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

The illusory potential of painting has been celebrated since ancient times, reflected acutely in the legendary challenge between the painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius, narrated in Pliny the Elder's first-century CE Natural History. According to this story, both artists agreed to a competition to settle who was the best—meaning most realistic—painter of their time. Zeuxis presented first; his painting of grapes in a bowl exhibited such realism that birds attempted to eat them. Filled with pride at his achievement, Zeuxis requested that Parrhasius lift the veil covering his work—only to find that the veil did not actually exist, but was painted by Parrhasius. Having been deceived by the work himself, Zeuxis conceded victory.

Pliny the Elder's tale has captured the imaginations of countless artists, historians, and thinkers, including French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who further explored the nature of appearance, its character of double deception, and the possibilities of the visible. Varo herself depicted curtains, as we see in one of her sketchbooks. Her interest, however, was always in how she could show more than the visible; even the simplest veil is charged with a supernatural presence.

Creación de las aves is more than just an allegory of the creative act; Varo reexamined, criticized, and redefined the hierarchy that had long privileged the attainment of visual similitude. There is no game of mimesis but rather an unveiling to realms beyond sight. The birds cease to simply represent elements of the world and instead reveal the transmutative nature of art—or the creative act—enacted through the gazes of the artist and viewers of the work. For Varo, verisimilitude—an artistic achievement that preoccupied artists throughout much Western history—was only a means to an end; art is a revelation, as are nature and science.

To facilitate the act of painting, Varo's bird-creator wears a three-stringed instrument around their neck from which the paintbrush extends. This representation of the artist recalls Russian Armenian philosopher and mystic George I. Gurdjieff's ideas about art, specifically his distinction between objective and subjective art. For him, objective art is the product of a fully conscious effort, and it is capable of making a precise impression to reveal profound knowledge. He focused mainly on his view that the universe is composed of vibrations in continuous movement; the cosmos is a scale of seven notes, each of which can be subdivided. In the method he developed at the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, music and dance occupied a central place in the quest to reach the higher state of consciousness, to reach the "cosmic octave." Varo's reference is explicit in the bird-creator: the act of creation must be a conscious and spiritual act—only then is transmutation possible.

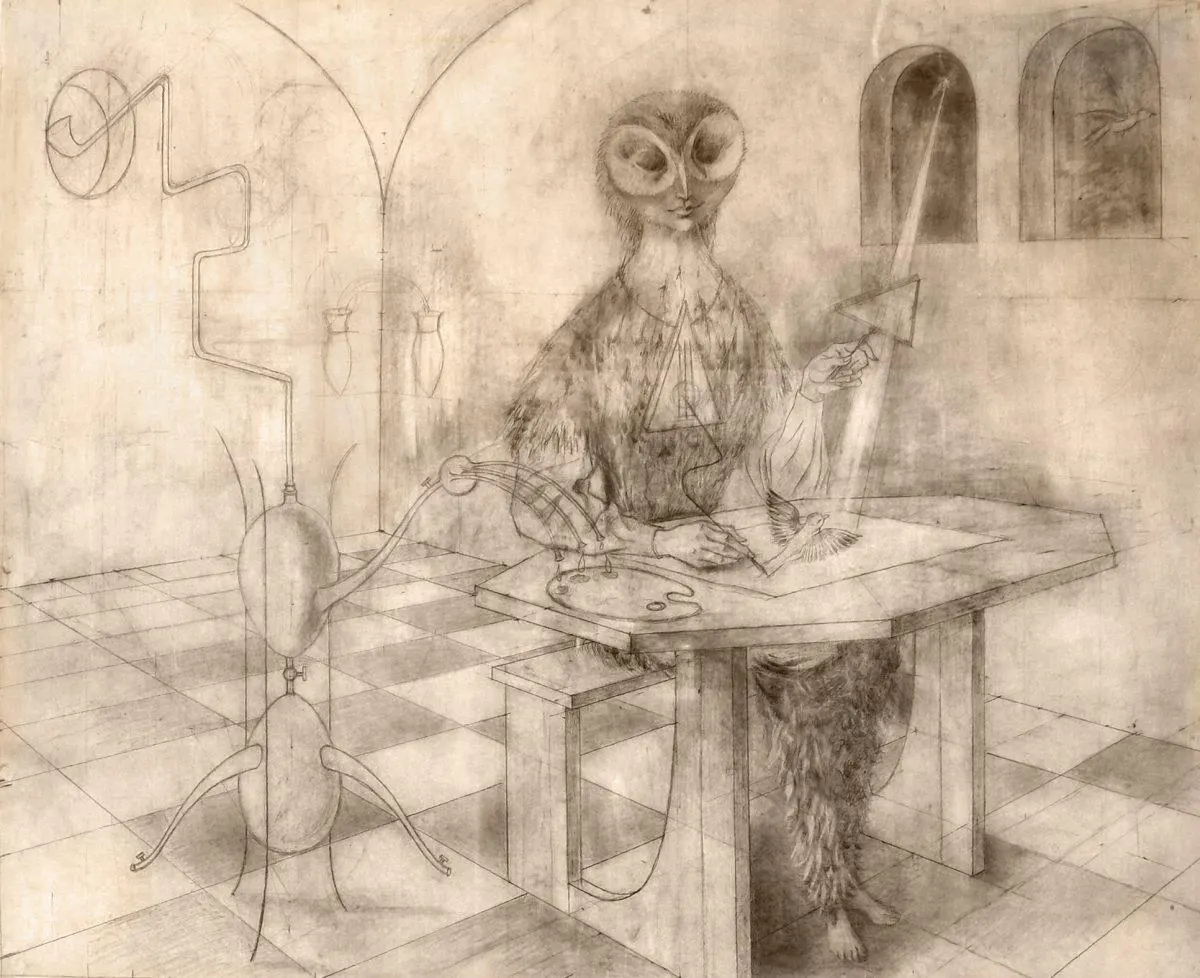

Remedios Varo, Preparatory drawing forCreación de las aves (Creation of the Birds), 1957. Graphite on translucent paper, 50 x 62 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

Curiously, in the preparatory drawing for the work, the coffee mill that we see in the background of the final painting is not present. Why did the artist include it in the final composition? This domestic element alludes to a process of transformation of material, converting the beans into granules, but it also suggests that the domestic sphere is a kind of laboratory for everyday life. As author Janet A. Kaplan has pointed out, Varo "concocted pseudo-scientific research in the form of recipes." In this light, the kitchen is the place of the alchemist and the scientist.

This conceptualization requires rereading the figure in Creación de las aves, whose form oscillates between two animal beings and whose gender is indeterminate. This ambiguity upends patriarchal understandings of what constitutes a creator, making space for an androgynous and animal creator who reflects the artist's broad ecofeminist view. It also allowed Varo to correlate and blend the wide-ranging sources that supported her aesthetic-scientific-natural ideal—especially alchemy, the development of the universe as theorized by English scientist Sir Fred Hoyle, and the debates that she followed in scientific magazines of the time. Varo's ideal is that of generous collaboration and interdisciplinary cross-mingling, not the compartmentalization, restriction, and exclusion typical of Western approaches to disciplines of knowledge (and art). If there is any hope, Varo situates it here, in the place where birds fly free—not as outwitted grape eaters but possibly as seers or, simply, as birds.