What is a formal analysis?

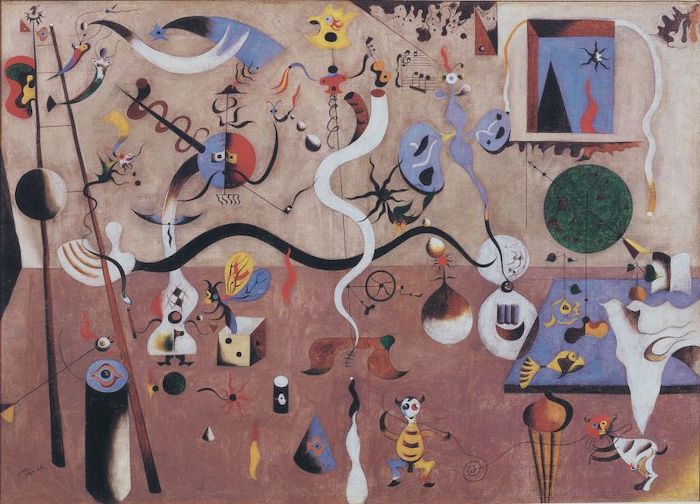

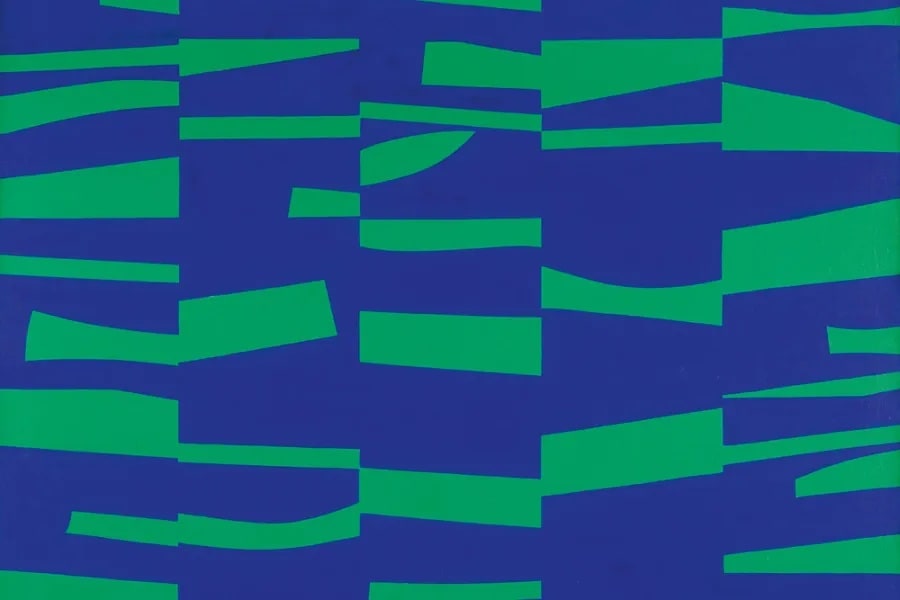

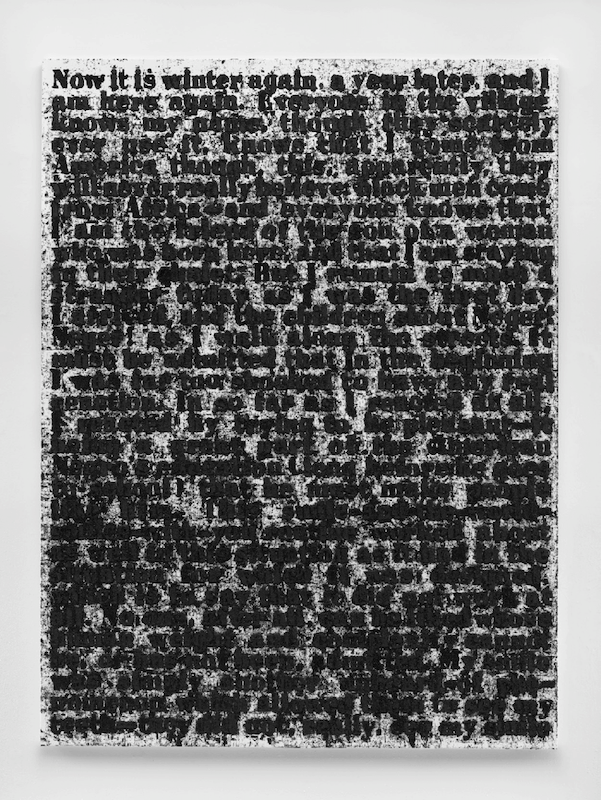

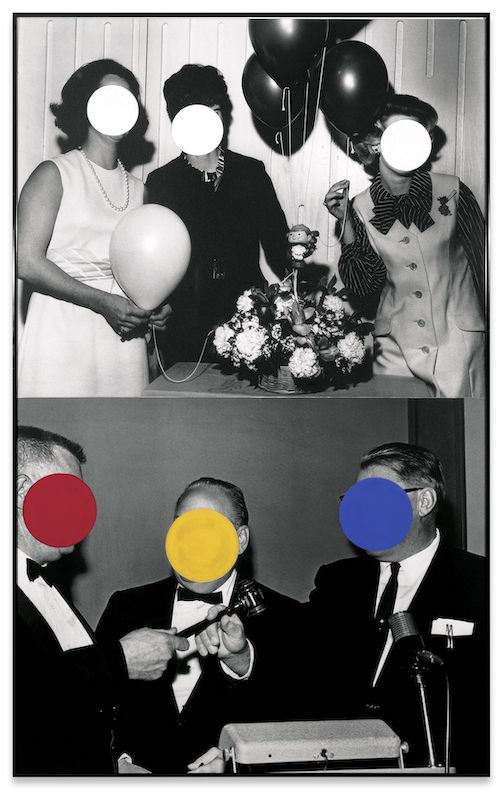

At its root, it's an examination of the forms (visual elements and qualities) that are discernible in an artwork or object. What an artwork looks like – including the ways it's made to look like it does – matters! These forms not only define the work's visual character, they also give it its expression, message, and meaning.

A formal analysis assumes a work of art is a purposefully made object, which has been created with a stable meaning (even though it might not be clear to the viewer), and the meaning or character of the work can be ascertained by studying the relationships between the work's visual elements and qualities.

-

Thomas Struth – Art Institute of Chicago II, Chicago (1990)

-

Imagine describing a work of art to someone who has never seen it before (assume they can't see it or look up a picture of it). By reading your formal analysis, that person should have a complete mental picture of what the work looks like.

Yet, the formal analysis is more than just a description, it makes a claim about the work, it says something about how its visual elements and qualities are constructed and what effects they have. A formal analysis needs a thesis statement that reflects your conclusions about the work. This statement is like the key takeaway of your analysis and is crucial because it establishes the tone for the entire paper and sets it apart from being just a plain description.

Moreover, think about what effect these visual properties have on you as a viewer. How does the work direct your attention? How does it guide you through the work, or communicate something to you? Even the subtle things matter. To cite a non-art, non-human example, there's a viral trend I love of dogs watching Bluey, an animated kids shows about a family of dogs. Dogs are colourblind, but the animators included tones that dogs can perceive - so there's loads of videos of dogs watching it, absorbed, and even having a moment 🥹 Think about how one formal element - colour - totally changes how these viewers engage with the image, not because they understand what's going on, but are literally seeing it in a way that affects their attention and emotions.

A formal analysis is not concerned with explaining the symbolic interpretation or historical meaning of a work. It is first and foremost an exercise in close-looking, and you may have to resist the urge to jump to interpreting what the artwork means. A visual examination of the work is the starting point for unpacking how the work's effects, meaning, and expression are constructed by understanding how the work is visually constructed.

The video below, Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker outline the process of visually analyzing artworks.

Video: How to do visual (formal) analysis

-

Recap: What is the goal of a formal analysis?

In short: to explain how the formal elements (the visual forms and stylistic qualities and effects) of an artwork affect the representation of the subject matter and expressive content. Here, the emphasis is on analyzing the formal elements, not conducting research or doing interpretation of symbolism or historical background.

-

Writing a thesis for a formal analysis:

Here, a thesis statement should provides a framework for your analysis while suggesting your interpretation of the work. A thesis does not necessarily involve a statement of argument or original insight but should let the reader know how the artist's formal choices affect the viewer.