The Great Mosque of Damascus By Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis, Smarthistory, May 15, 2015.

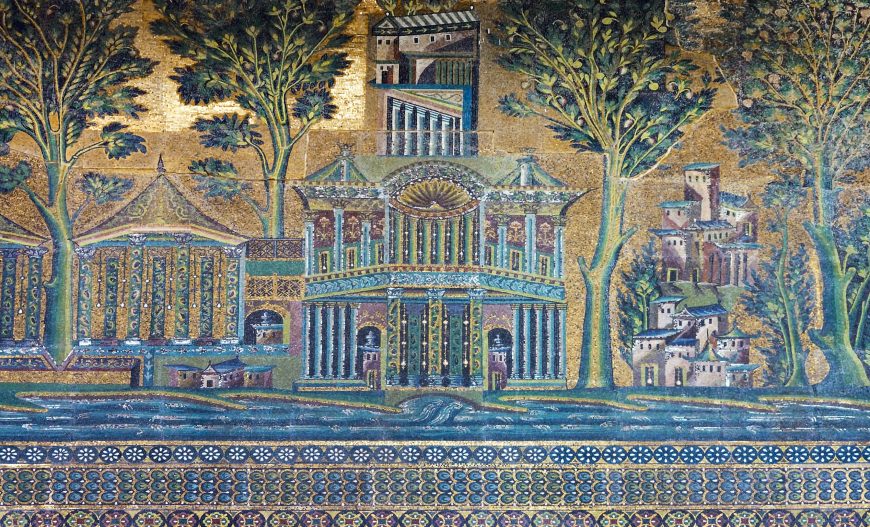

To understand the importance of the Great Mosque of Damascus, built by the Umayyad caliph, al-Walid II between 708 and 715 C.E., we need to look into the recesses of time. Damascus is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world, with archaeological remains dating from as early as 9000 B.C.E., and sacred spaces have been central to the Old City of Damascus ever since. As early as the 9th century B.C.E., a temple was built to Hadad-Ramman, the Semitic god of storm and rain. Though the exact form and shape of this temple is unknown, a bas-relief with a sphinx, believed to come from this temple, was reused in the northern wall of the city’s Great Mosque.

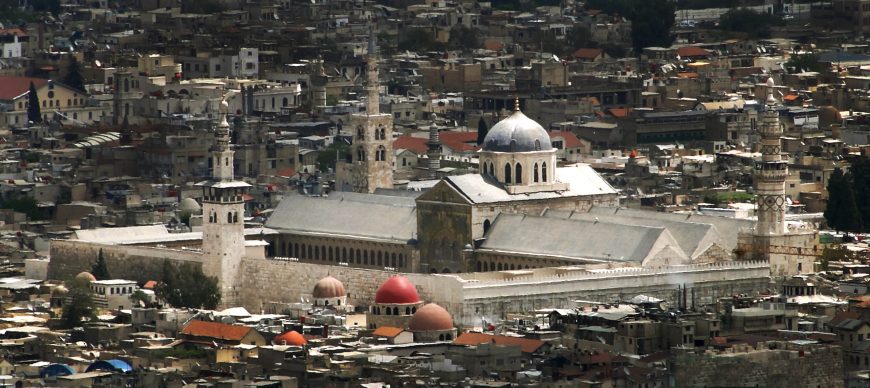

Distant view of the Great Mosque of Damascus, photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0

Location of Great Mosque of Damascus

From Zeus to Saul

Alexander the Great marched through Syria on his way to Persia and India and while he likely passed through Damascus, it was his successors—the Ptolemies and the Selecuids—who would shape Syria. Until 63 B.C.E., Damascus would remain under the political control and cultural influence of these Greek dynasties. While almost nothing survives archaeologically from this period, Greek became the dominant language and the culture became Hellenized (influenced by Greek culture). At this time, the temple of Hadad was converted into a Temple of Zeus-Hadad. Zeus was a natural choice for assimilation; he ruled the Greek pantheon and was associated with weather and, of course, thunderbolts. Many Greek (and later Roman) gods were combined with local gods across the lands controlled by the Greeks and then the Romans. This allowed the conquering culture to integrate their new subjects into their religion, while also accepting local traditions—thus helping to make new foreign masters more agreeable to subjugated locals. The Zeus-Hadad temple dominated the Greek city and was connected by a main thoroughfare to the new agora, or market area, located to the east. At the center of a temenos, an enclosed and sacred precinct, stood the temple to Zeus-Hadad, which had a cella (the room in which a statue of the god stood).

After the Greeks came the invading Roman armies (led by Pompey in 63 B.C.E.). Under Herod the Great (the local pro-Roman ruler), the city of Damascus was transformed. Herod built a theater whose remains can still be seen in the basement and ground floor of a house called Bayt al- ‘Aqqad (now the Danish Institute). The temple was modified at this time when two concentric walls were added to enclose the precinct (or peribolos) of the temple and two monumental gates, or propylaea, were added on the western and eastern ends of the precinct which now measured 117,000 square feet. At its center was the temple with a cella for the worship of Jupiter-Hadad. It was now a truly monumental temple. The western gate was refurbished and embellished under the Roman Severan dynasty (193–235 C.E.), additions that remain visible today.

Although the great temple to Jupiter marked the spiritual heart of the city for several centuries, just as it was completed, a new cult to a single God was developing: Christianity. Saul, or Paul as he is known after his conversion, is said to have converted on the road to Damascus (Acts 9.1–2; 9.5–6). Blinded by a light, he was led to the home of a Jew named Judas on Straight Street, the decumanus or main east-west street in Damascus. Ananias had a vision that told him to go and care for Paul and when he touched Paul at Judas’ house, the scales fell from Paul’s eyes and he could see.

Unsurprisingly, once Christianity was widely adopted in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, the temple to Jupiter was once again converted, this time into a cathedral dedicated to John the Baptist. This church is attributed to the Emperor Theodosius in 391 C.E. The exact location of the church is unknown, but it is thought to have been located in the western part of the temenos. It was probably one of the largest churches in the Christian world and served as a major center of Christianity until 636 C.E. when the city was once again conquered, this time by Muslim Arabs. Damascus was a key city, as it provided access to the sea and to the desert. When it was clear that the city was going to fall, the defeated Christians and conquering Muslims negotiated the city’s surrender. The Muslims agreed to respect the lives, property and churches of the Christians. Christians retained control of their cathedral, although Muslim worshippers reportedly used the southern wall of the compound when they prayed towards Mecca.