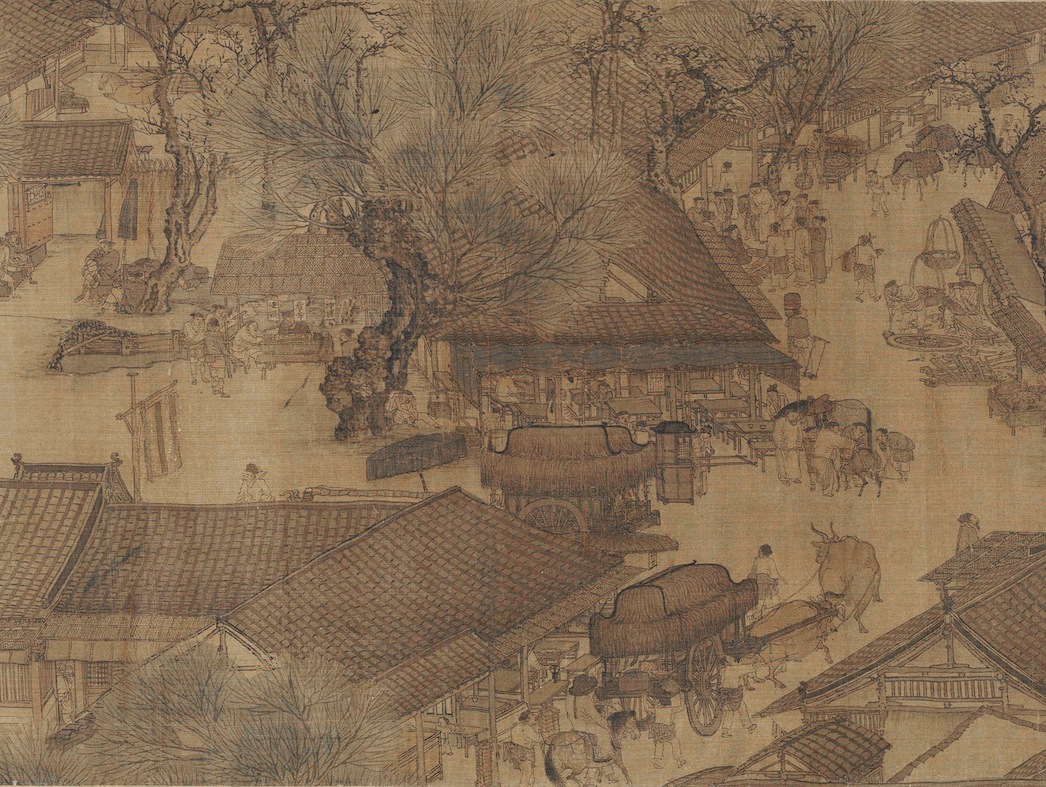

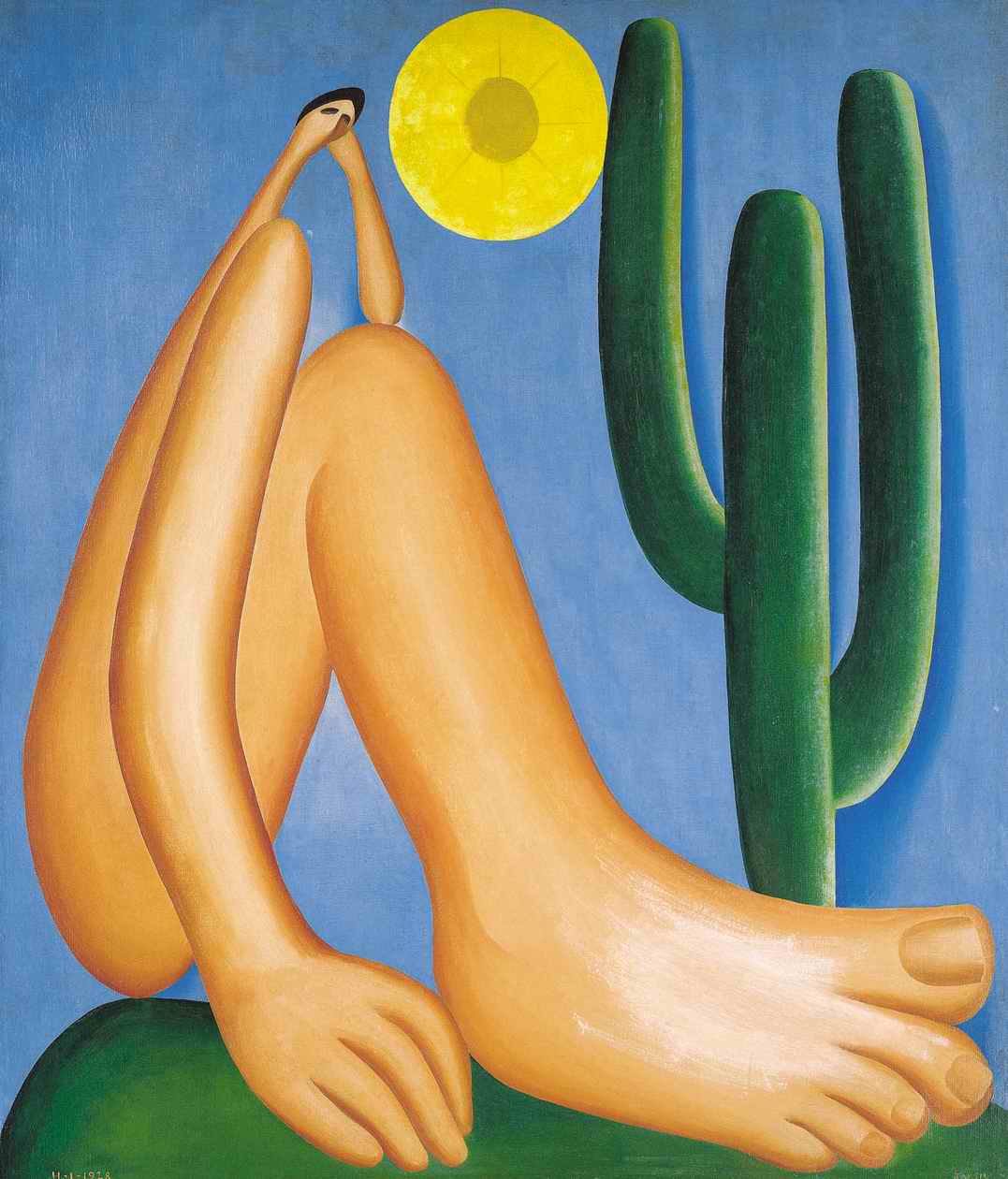

Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporú From MoMA, "Tarsila do Amaral. Abaporu. 1928" and Maria Castro, "Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporú," in Smarthistory, October 11, 2021.

Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporú, 1928. Oil on canvas, 85 x 73 cm. Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires.

Man Who Eats

Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral painted Abaporú in her São Paulo studio early in 1928. It depicts a seated nude figure in profile who is of ambiguous age, gender, and race. His bare right foot and hand are firmly planted on the ground. His right knee is bent towards his chest, obscuring any view of a left leg or foot. His left elbow rests on the bent right knee, propping up a very small head. This figure is painted from an extremely low perspective, which causes his body to appear distorted. His right hand and foot are enormous, while his head and upper torso are quite small. The figure appears to be outdoors, sitting on a green surface from which rise a large cactus and a yellow sphere, against a blue background.

Tarsila, as she is commonly known in Brazil, was one of the foremost painters of São Paulo’s modernist movement in the first half of the twentieth century. She is best known for her innovative paintings of the 1920s, when she was actively engaged in the development of a new visual language of Brazilian modernism.

In January of 1928, Tarsila presented Abaporú as a birthday gift to her husband, the writer and modernist theorizer Oswald de Andrade. By their own accounts, de Andrade was fascinated by the painting and proclaimed that he would make a movement around it. Consulting a seventeenth-century dictionary of Tupi-Guarani Indigenous languages written by the Jesuit missionary Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, Tarsila named the painting “aba-poru,” a combination of words that has been roughly translated to “man who eats.”

Abaporú, which is today in the collection of the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires (MALBA), has become an icon of twentieth-century Brazilian art. This is both because the painting employs unique visual strategies and also because it inspired the writing of one of the most important documents in Brazilian art of the twentieth century: the Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibalist Manifesto, 1928), written by de Andrade.

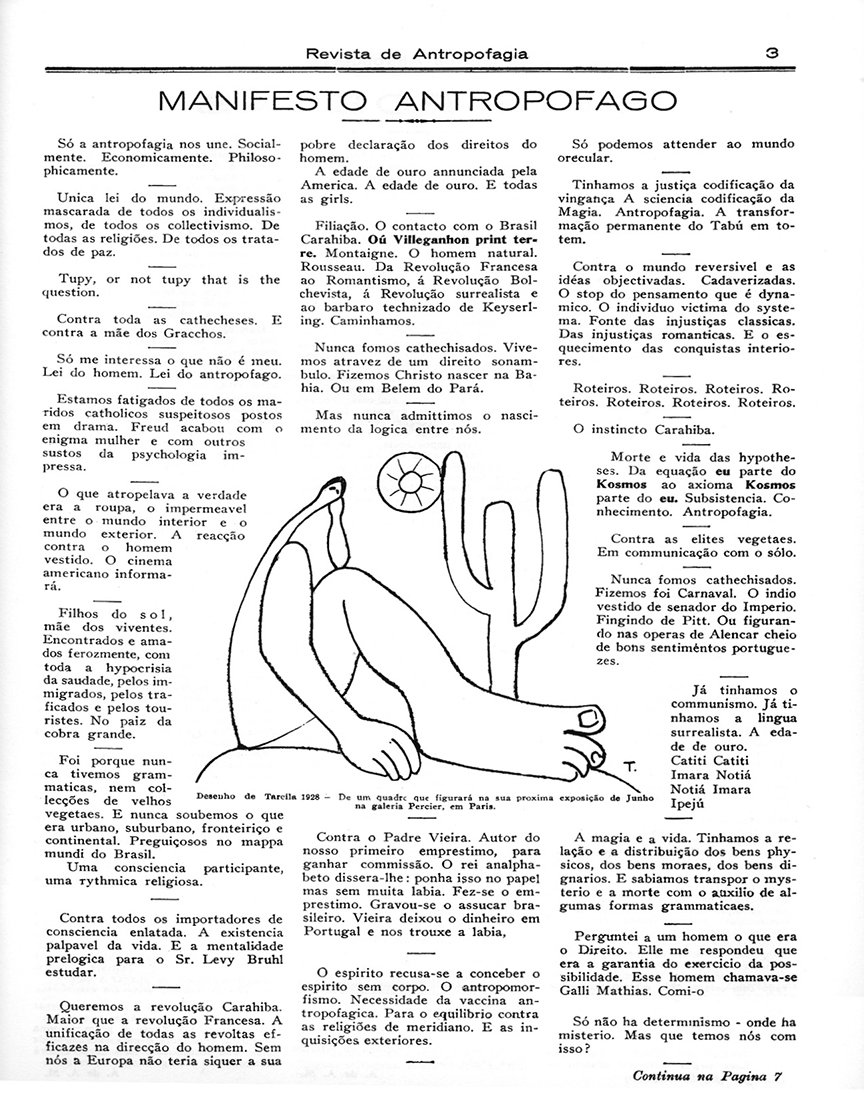

Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibalist Manifesto), in the Revista de Antropofagia (Journal of Anthropophagy), May 1928.

The Cannibalist Manifesto

With the now famous phrase “Tupi or not tupi, that is the question,” de Andrade opens his Cannibalist Manifesto making a reference to Shakespeare’s Hamlet while asking a question about Brazilian cultural identity. Tupi was one of the largest Indigenous linguistic groups in pre-conquest Brazil, encompassing many tribes that lived along the region’s Atlantic coast. Some were said to practice ritual anthropophagy at times of war; practices that aroused the interest, and often imagination, of early European explorers and colonizers. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artists such as Theodor de Bry and Albert Eckhout explored the subject of anthropophagy in fantastical prints and paintings that depicted Indigenous Brazilians consuming or carrying severed limbs.

Addressing this colonialist preoccupation with cannibalism, in his manifesto de Andrade employs the concept of anthropophagy as a metaphor for cultural consumption. He argues that artists should be free to cannibalize, or appropriate, the many cultural influences that surrounded them in modern Brazil—be they Indigenous, popular, or foreign. After a process of digestion, or synthesis, he believed this consumption would yield new cultural products, both original and genuinely Brazilian.

The manifesto was published in the first issue of the Revista de Antropofagia (Journal of Antropophagy) in May, 1928. In its original publication, it was illustrated by a line drawing of Tarsila’s Abaporú.