Tā Moko Encyclopedia entry from Margo DeMello, Faces around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia of the Human Face (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2012).

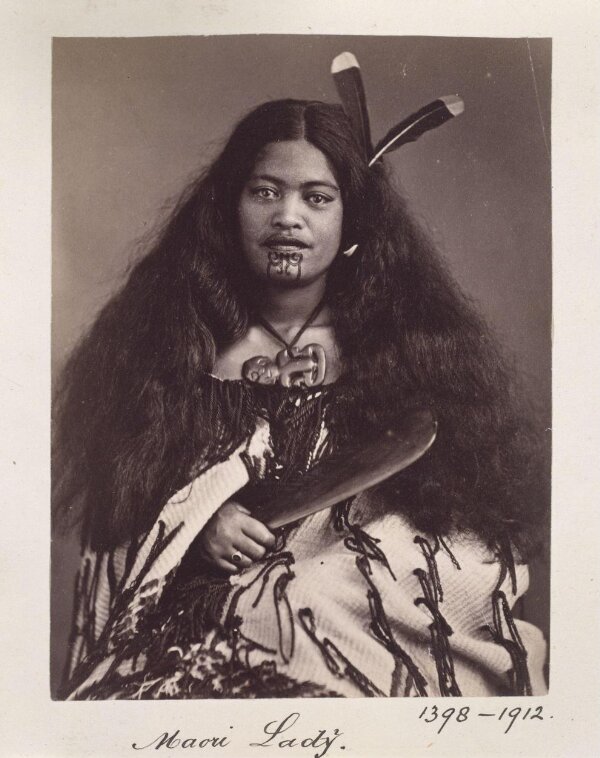

Foy Brothers, Pare Wātene, c. 1871–1909. Photograph, albumen print. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The native people of New Zealand, called the Māori, are known around the world for their tattooing. Although their tattoos do not cover as much of the body as many South Pacific people such as the Samoans, the Māori developed their own unusual style of tattooing, covering the face and the buttocks. First described by Captain James Cook in 1769, Māori tattooing remains one of the most unique and beautiful of all tattoo traditions.

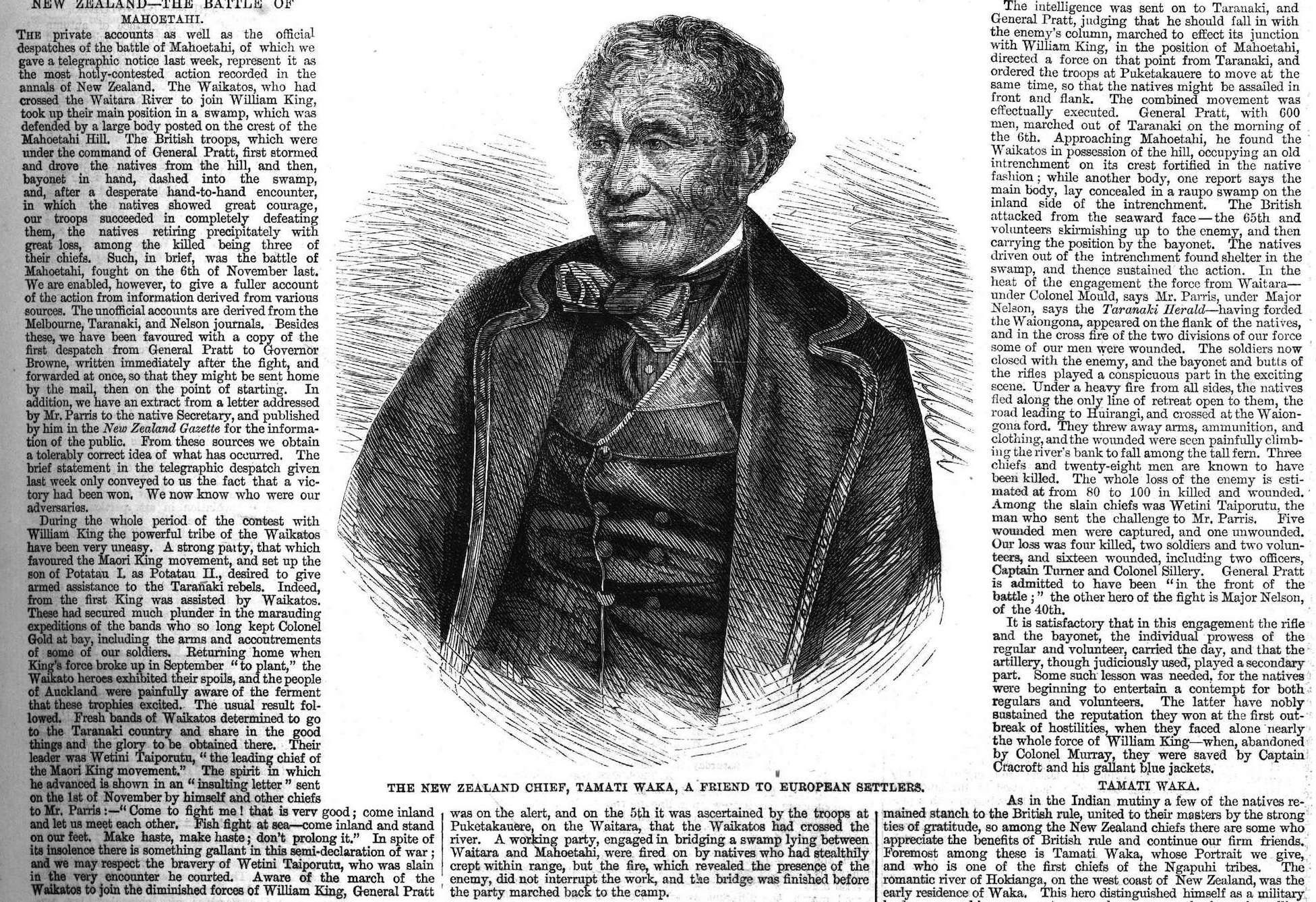

The moko is the curvilinear facia tattoo worn by Māori men and women as a sign of status as well as affiliation, and only high-status Māori and warriors at one time were tattooed. Women's tattoos were originally limited to the lips and sometimes other parts of the body or forehead; in the 19th century, the spiral chin tattoo was developed. Men could wear the moko, or, if they had their bodies tattooed, the tattoo extended over the area between the waist and the knees, primarily covering the buttocks.

The tattoo design was first drawn onto the skin, and then carved into the skin with a tool known as uhi whaka tataramoa, which operated much like wood carving to which it can be related both in design and technique. The tattooist, who was always a man, literally carved the design into the skin. After cutting the skin, pigment was rubbed into the wound.

The procedure was said to be incredibly painful, and caused so much facial swelling that, after tattooing, the person could not eat normally, and had to be fed liquids through a funnel. During the lengthy tattoo, as well, the tattooed person could receive liquid food through the tunnel, thus keeping the contaminating food from the wounds. A woman's moko, which covered the chin and lips, could take one or two days to complete. A man's moko, which covered the whole face, was done in several stages over several years and was an important rite of passage for a Māori man; without the moko, the man was said to not be a complete person.

Gottfried Lindauer, Pare Wātene, 1878. Oil on canvas, 102.8 x 85.5 x 7.0 cm. Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland.

Unlike tattoos in Polynesia and elsewhere, which have designs that are worn by everyone of the same tribe, clan, or tank, Māori tattoos were totally individual. While they did indicate a man's social and kinship position, marital status, and other information, each moko was like a fingerprint, and no two were alike. Māori chiefs even used drawings of their moko as their signature in the 19th century. Because the moko, in part, signified rank, different designs on both men and women could be read as relating to their family status, and each of the Māori social ranks carried different designs. In addition, some women who, due to their genealogical connections, were extremely high status, could wear part of the male moko.

As in Marquesan tattooing, Māori facial designs were divided into four zones (left forehead, right forehead, left lower face, and right lower face) and these further divided, giving an overall symmetry to the design. The right side of the face conveyed information about the father's rank, tribal affiliations, and position. The left side of a face, on the other hand, gave information about the mother's rank, tribal affiliations, and position. Each side of the face is also subdivided into eight sections, which contain information about rank, position in life, tribal identification, lineage, and more personal information, including occupation or skill.

Tattooing styles varied from tribe to tribe and region to region, as well as love time. Cook, for example, noted that the men on one side of an inlet were tattooed all over their faces, whereas the men on the other side of the inlet were only tattooed on the lips. He also noted that some moko did not include the forehead but only extended from the chin to the eyes. Also, Cook's men noted that there was at least one man at that time who had straight vertical lines tattooed on his face, combined with spirals, as well as two elderly men with horizontal lines across their face. Tattoos of this sort were never again seen on subsequent visits. And by the 19th century, different styles of moko were seen, including both the classic curvilinear styles as well as vertical and horizontal parallel lines.

The Māori had a tradition of preserving the tattooed heads of deceased persons of nobility in order, it was presumed, to keep alive the memory of the dead. The heads were also held to be sacred, in that they continued to possess the deceased's mana, or magical quality. But in 1770, just a year after initial contact, Europeans became interested in these tattooed heads, and initiated a heads-for-weapons trade that lasted until 1831, when it was banned by the colonial authorities.

The first dried head to be possessed by a European was acquired on January 20, 1770. It was brought by Joseph Banks, who was with Cook's expedition as a naturalist, and was one of four brought to board the Endeavour for inspection. It was the head of a tattooed youth of 14 or 15, who had been killed by a blow to the head.

The trade became especially scandalous because during the tribal wars of the 1820s, when European demand for the heads was at an all time high, war captives and slaves were probably tattooed, killed, and their decapitated heads sold to European traders. As the traffic in heads escalated, the Māori stopped preserving the heads of their friends, so that they wouldn't fall into the hands of the Europeans. Evidently, it also became dangerous to even wear a moko, as one could be killed at any time and have one's head sold to traders. By the end of the head trade in the 1830s, the moko was dying out, due to missionary activity.

Like Hawaiian and Tahitian tattooing, Māori tattooing was also influenced by European contact. On Cook's first visit to New Zealand, the ship artist, Sydney Parkinson, drew pictures of the moko, exposing Europeans for the first time to Māori and their art, and, inciting the interest in tattooed heads that would follow. Tattoo techniques changed as well as a result of contact. Originally, the Māori applied their wood carving techniques to tattooing, literally carving the skin and rubbing ink into the open wounds. After European contact, sailors brought metal to the Māori, enabling them to adopt the puncture method found in the parts of Polynesia.

After European contact, the moko became associated with Māori culture as a way for the native people of New Zealand to distinguish themselves from the Europeans who had settled there, but by 1840, due to missionary activity, the male moko was falling out of fashion. It was revived briefly during the wars against Europe from 1864 to 1868, but by the turn of the century, there were only a handful of tattooed Māori alive. Ironically, it was during the period in which the male moko was declining that the female chin moko was gaining in popularity as a symbol of identity.

Since the late 20th century, some Māori have begun wearing tā moko again as an assertion of their cultural identity. A few Māori tattoo artists are reviving traditional methods of applying tā moko, but most use electric machines.

Related References

- Friedlander, Marti and Michael King. Moko: Māori Tattooing in the Twentieth Century. Auckland: David Beatman, 1999.

- Gathercole, Peter. "Contexts of Māori Moko." In Marks of Civilization, edited by Arnold Rubin, 171–78. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1988.

- Nicholas, Thomas, ed. Tattoo: Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Simmons, D. R. Tā Moko: The Art of Māori Tattoo. Auckland: Reed Books, 1986.