Tsuu T'ina (Sarcee) From Eung-do Cook, "Tsuut'ina (Sarcee)," The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 1, 2012.

The Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee) are a Dene (or Athabaskan) First Nation whose reserve borders the southwestern city limits of Calgary, Alberta. The name "Sarcee" is believed to have originated from a Siksikáí’powahsin (Blackfoot language) word meaning boldness and hardiness. The Sarcee people call themselves Tsuu T’ina (also Tsuut'ina and Tsúùt'ínà), translated literally as "many people" or "every one (in the Nation)."

Traditional Territory

According to oral tradition, the Tsuu T’ina split from a northern nation, probably the Dane-zaa, and moved to the plains, where they have maintained close contact with the Siksika, Cree and Stoney. Their acculturation to the plains culture distinguishes them from other northern Dene people, but they have retained their language, often known as Sarcee.

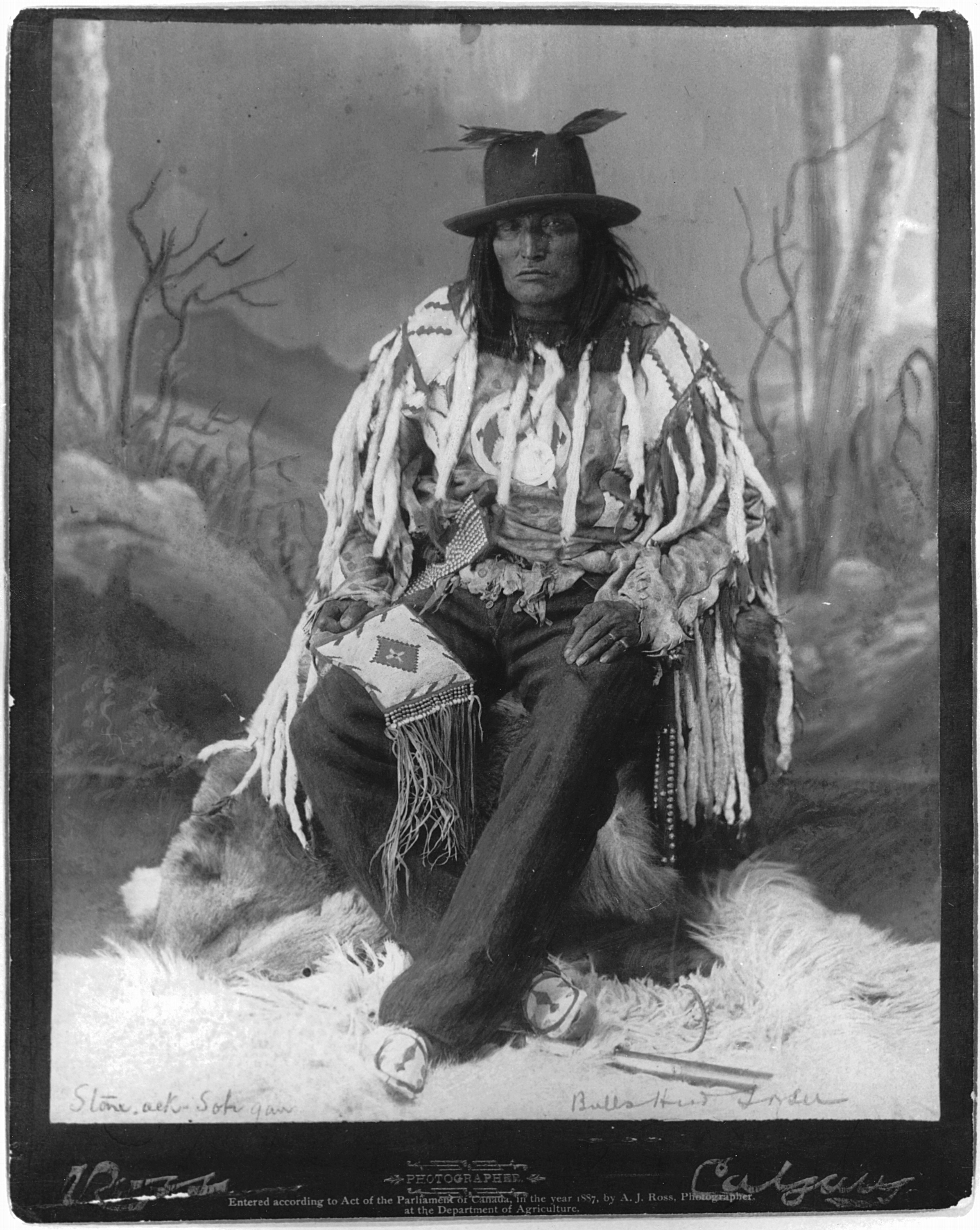

Today, Tsuu’tina territory is in southern Alberta, bordering the southwestern city limits of Calgary. In 1877, well-known leader Chief Bull’s Head reluctantly signed Treaty 7, which created the 280 km2 reserve on which the Tsuu T’ina now live.

Tsuu T'ina Chief (Stone-Ack-Soh-Gan or Chief Bull's Head), 1887. Photograph by Alexander James Ross, silver salts and watercolour on paper mounted on card, albumen process, 22.9 x 18.3 cm. McCord Stewart Museum, Montreal.

Bull’s Head, a Tsuu T’ina Chief

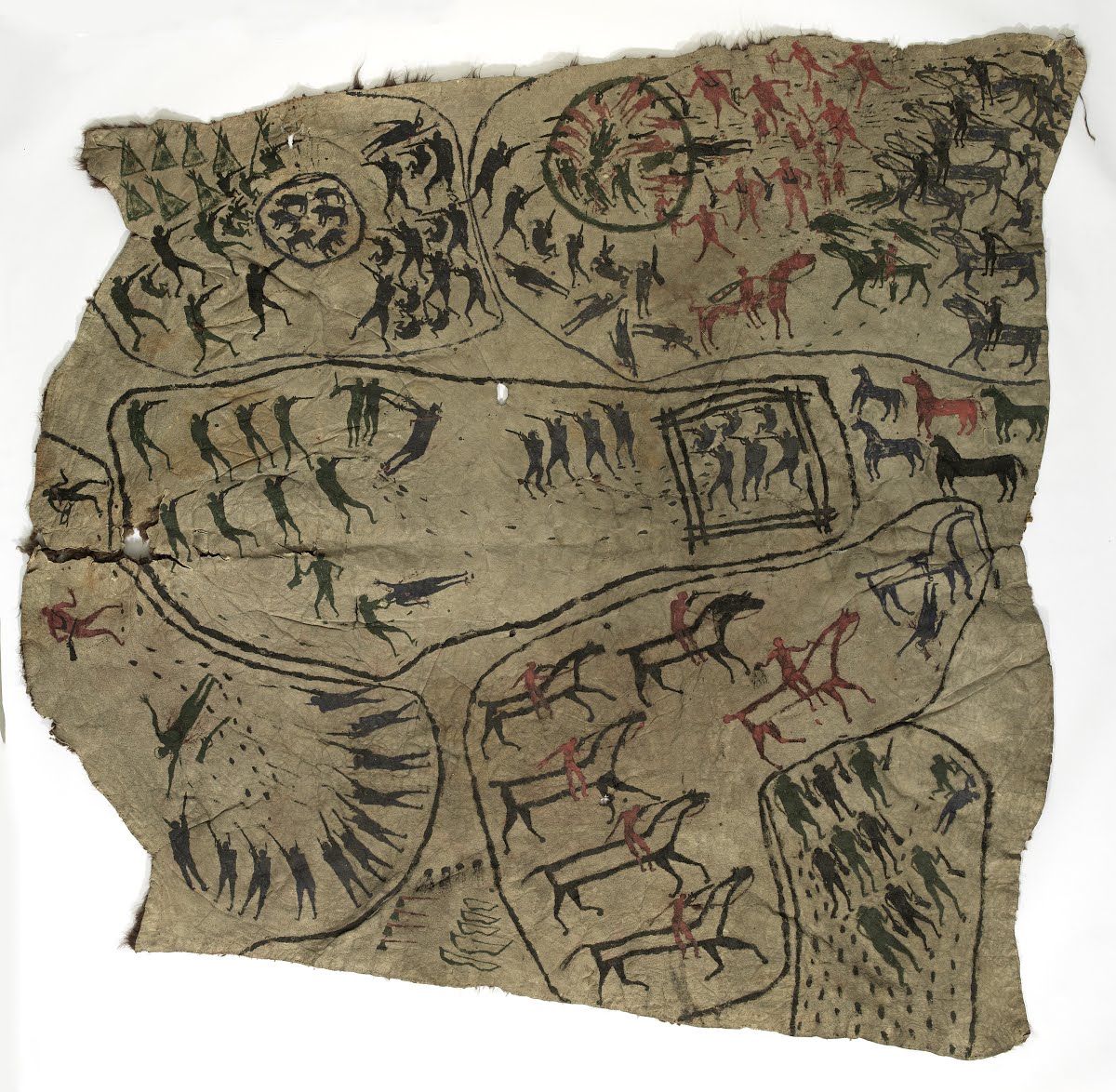

Born around 1833, Chief Bull’s Head belonged to the Tsuu T’ina tribe, formerly called the Sarcee. After mid-century, when inter-tribal warfare reached high intensity, Bull’s Head became the leading warrior of his tribe. His war deeds are recorded on the painted buffalo hide displayed behind you. After his brother died in battle in 1865, Bull’s Head succeeded him as chief of the tribe and led the Tsuu T’ina until his death in 1911.

In 1877 Bull’s Head signed Treaty No. 7 with the Dominion of Canada on behalf of his people, who numbered 255. Several years later, the Tsuu T’ina settled on a reserve twelve kilometers from the center of present day Calgary. Despite devastating social and health problems, and great pressure to sell parts of their land, Bull’s Head ably led the Tsuu T’ina into the twentieth century united as a people and with their reserve intact.

Traditional Life

Prior to life on the reserve, the Tsuu T’ina camped in tipis and hunted along the edge of the forest during the winter. During the summer, all bands met in the open prairie to hunt bison, collect berries and engage in ceremonies, dances and festivals.

When anthropologist Diamond Jenness visited the Tsuu T’ina reserve in 1921, the nation consisted of five bands: Big Plumes, Crow Childs, Crow Chiefs, Old Sarcees and Many Horses. Before they were confined to the reserve, each band was led by a chief. Today, the band is governed by an elected chief and counsellors.

Language

The Tsuu T’ina language (often known as Sarcee) is an Athabaskan/Dene language of northern Canada. It is considered endangered; according to the 2016 Statistics Canada census, only 150 people identify having knowledge of Sarcee. Various institutions and community programs are working to preserve and protect the language. In 2011, the University of Calgary developed a program in association with the Tsuu T'ina Gunaha Institute to help revive the language.

Watch the video below to hear more about the Tsuu T’ina language.