Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on What It Means To Be Kenyan Originally posted on Google Arts & Culture.

In the interview below, Nigerian linguist and writer Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún explores Kenyan identity with the celebrated author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

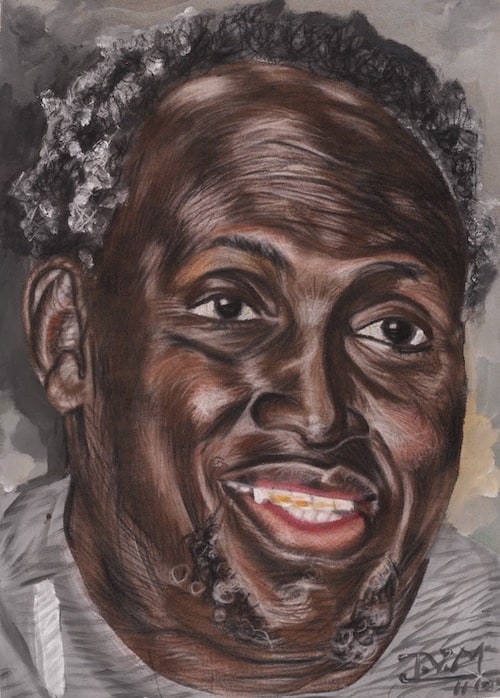

Portrait of Ngugi wa Thiong'o, from the collection of Steve Biko Foundation.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, born in January of 1938, is a foremost Kenyan writer, professor, and language activist — probably the best known Kenyan writer today. His renown, work, and activism has won him fans and several awards worldwide for his novels, plays, short stories, and essays.

In 2016, his short story, Ituĩka Rĩa Mũrũngarũ: Kana Kĩrĩa Gĩtũmaga Andũ Mathiĩ Marũngiĩ (The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright) became the most translated African short story, currently in over fifty languages. It was written originally in Kikuyu, the writer’s first language—which all his stories since the seventies have been written in, before they get translated into other languages.

I myself have translated the story into Yorùbá, having met the writer at a literary festival in Abẹ́òkuta, Nigeria, in 2016. I have since collaborated with him on other projects enough to call him a mentor, father-figure, and friend. In this interview, I talk to him important cultural issues, his career, and Kenya, his native land.

How would you describe "the people of Kenya" to someone who has never met them or even heard about the country?

Beautiful. Talented. Hardworking. Enterprising. The country is a vibrant space of the different cultural streams of African, Asian, and European origins. Its landscape and history have become part of the global imagination.

What does "identity" mean to you?

Identity is an ever changing unity of difference and sameness; particularity and universality. Identity is the imagined container of multitudes. I am Gĩkũyũ, meaning I share a certain history with all who call themselves Gĩkũyũ, but I am also Kenyan, meaning I share a geographic and historical space with all other Kenyans. I am African. I am black. I’m a citizen of the world.

In which way has the notion of your identity changed over the years?

It follows from the above that notions of identity, especially the name we give to it, change all the time. The particulars of experience change but the universal element of being, bound up in the particular, remains. Particularity is the form of being. Universality is the commonality of being. Identity is their unity.

How has being part of the Kikuyu community influenced your life and outlook?

I have shared my story in my memoirs: Dreams in a Time of War; In the House of the Interpreter; Birth of a Dreamweaver, and Wrestling with the Devil. I am still writing it through my actions. I was born in a home of four mothers, one father, and several siblings. My biological mother, Wanjikũ, is the most important influence on my life. She always wanted to know if I had tried my best, in whatever I did. But I am also a product of Gikuyu history and culture.

Today, 44 communities are officially registered by the Kenyan government and there are conversations about adding more to the list. Is there an object or a location that you consider to be a symbol of all these communities coming together?

We are a people just like any other peoples of our globe. But as Kenyan peoples, we share a common history of struggle against colonialism. I grew up within the wider history of resistance to British colonial state, which, led by the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (the one the British misnamed Mau Mau) helped bring about our Independence in 1963. We share aspiration for a Kenya in which every child has access to adequate food, housing, education, and health.

How would you define the identity of Kenya as a nation today?

The Kenyan identity is a work in progress. We struggle to be the best that Kenya can be. For this, we have to continue to struggle to secure our economic, political, and cultural base, all threatened by largely Western financial, and other, corporations. We have to continue to struggle against the gross social and income inequalities within our own country.

What is your favourite saying in any Kenyan language and why?

Gũtirĩ ũtukũ ũtakĩa: “There is no night so long that will not see the light of dawn.” My mother, Wanjikũ, used to tell me this proverb. In times of challenges and adversity, I always recall the saying to instill in me resistance against succumbing to the negative. The saying is an expression of optimism.

Additional Resource: Learn about the communities of Kenya.

-

Turkana festival, from the collection of the National Museums of Kenya.

-

Lake Turkana, from the collection of the National Museums of Kenya.