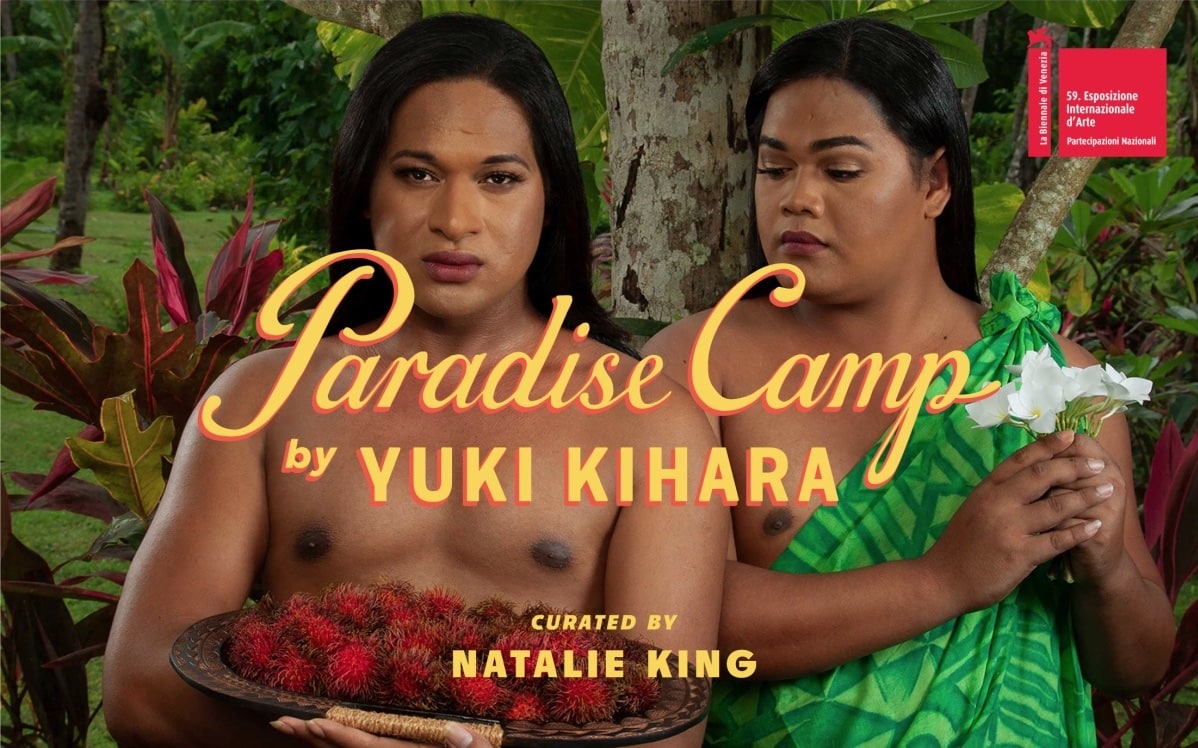

Beyond Gender: Indigenous Perspectives, Fa’afafine and Fa’afatama from Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, "Beyond Gender: Indigenous Perspectives, Fa'afafine and Fa'afatama.

In fact, numerous Indigenous communities around the world do not conflate gender and sex; rather, they recognize a third or more genders within their societies. Individuals that identify as a third gender many times have visible and socially recognizable positions within their societies and sometimes are thought to have unique or supernatural power that they can access because of their gender identity. However, as European influence and westernized ideologies began to spread and were, in many cases, forced upon Indigenous societies, third genders diminished, along with so many other Indigenous cultural traditions. Nevertheless, the cultural belief and acceptance of genders beyond a binary system still exist in traditional societies around the world. In many cases, these third gender individuals represent continuing cultural traditions and maintain aspects of cultural identity within their communities.

Within a Western and Christian ideological framework, individuals who identify as a third gender are often thought of as part of the LGBTQ community. This classification actually distorts the concept of a third gender and reflects a culture that historically recognizes only two genders based on sex assigned at birth—male or female—and anyone acting outside of the cultural norms for their sex may be classified as homosexual, gender queer, or transgender, among other classifications. In societies that recognize a third gender, the gender classification is not based on sexual identity, but rather on gender identity and spirituality. Individuals who identify with a cultural third gender are, in fact, acting within their gender/sex norm.

Fa’afafine and Fa’afatama, Samoa

Image of a Taupou Fa'afafine Artist by Milena Acosta

Many third gender individuals hold integral roles within societies and are well respected for their strength, hard work, and ability to discuss taboo topics. On the island of Samoa, there are four recognized cultural genders: female, male, fa’afafine, and fa’afatama. Fa’afafine and fa’afatama are fluid gender roles that move between male and female worlds. These third and fourth gender groups tend to care for elders in the community and educate others about sex, a topic considered taboo in public conversations for male and female genders.

One of the lasting cultural performances both preserved and revamped by fa'afafine and fa'afatama is the dance of the taupou. The taupou, or ceremonial hostess typically selected by the high chief in the village, is charged with representing and entertaining visitors. Traditionally, the taupou's dignity and grace expressed the ideals of appropriate female behavior. These displays were particularly favored by Christian missionaries that idealized the taupou's "virginal" and virtuous qualities. Today, when fa'afafine and fa'afatama participate in pageants, they will sometimes take on the role of the taupou, displaying grace and femininity while also making a caricature of the Christian-colonial ideal through sexual humor and body language. This take on the taupou's performance demonstrates the unique ability for fa'fafine and fa'afatama to transcend gender roles and leverage their skills to open the door for discussion on taboo subject through humor.

-

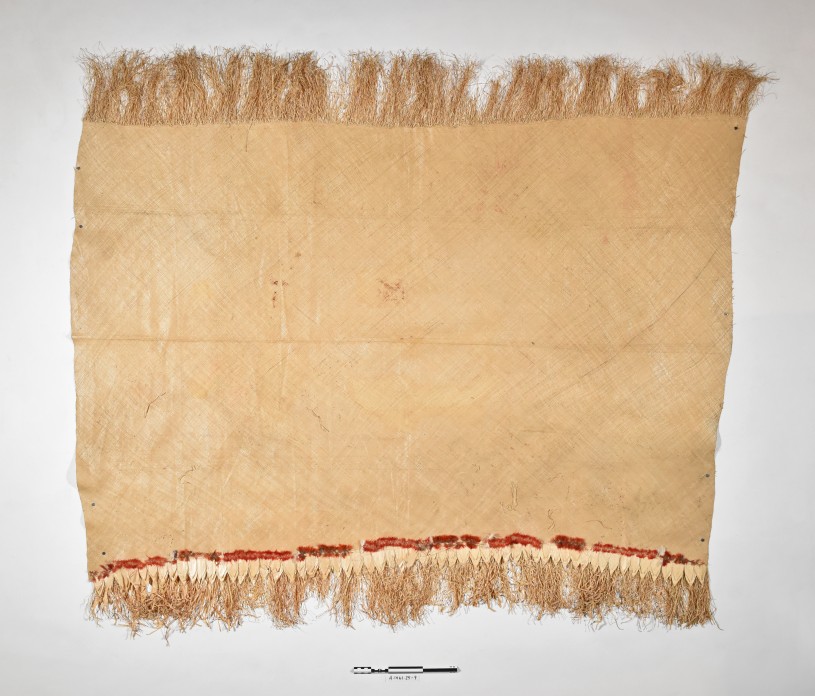

Finely woven Samoan mat, collected before 1925. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

-

Sperm whale tooth necklace from Fiji, collected in the 1890s. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

-

The club pictured was collected in Samoa between 1908–1910. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

As ceremonial hosts, taupou wear traditional Samoan dress, such as the ʻie tōga which is a finely woven mat worn tightly wrapped around the body. These mats traditionally have unwoven fringe at the edge and a strip of red feathers.

Crucial to the outfit is the ula nifo, a whale tooth necklace, a status symbol usually restricted to chiefs and their offspring, and likely an element held over from the days when the taupou was only performed by the virgin daughter of a chief. This necklace is made of sliced sperm whale teeth, and it was collected in Fiji in the 1890s. At that time the collector noted, “this ornament has the same relative value as a diamond necklace…” indicating that this type necklace was highly prized by many Polynesian cultures.

Miss Samoa Fa'afafine 2018–2019, Barbara Tino Tiufea Vaa.

Fa’afafine and Fa’afatama still thrive today.

In today’s dances, the taupou will carry a lightweight replica of a nifo‘oti, a large club modeled after cane knives of early nineteenth-century English and American whalers. Carrying these during the dance is reminiscent of pre-battle performances where heirloom clubs were artfully twirled and thrown to demonstrate the warrior’s prowess. This club was collected in Samoa between 1908–1910.

Today, one of the ways fa’afafine and fa’afatama contribute to the care of elders is by participating in the popular beauty pageants whose proceeds go to charities like Mapuifagalele, Western Samoa’s home for the aged. In these pageants, fa’afafine and fa’afatama often perform the dance of the taupou. The portrayal by fa’afafine and fa’afatama of taupou in these beauty pageants carries a different kind of message than when it was traditionally performed by the virgin daughter of a chief; however, the grace, beauty, and poise of the taupou continues to be the core message of the dance.

-

Fiafia show at Aggie Grey's with taupou, ceremonial hostess at center.

-

Samoan Fa'afafine Association.

-

Samoan Fa'afafine Association.

Further Reading

Samoan Queer Lives looks at the experiences of fa’afafine living in Samoa and beyond from the 1940s to the present day through autobiographical stories. The book is written by and edited by fa`afafine, Dan Taulapapa McMullin and Yuki Kihara, and includes personal stories that cross lines of gender, culture, professions and geography. Author royalties are donated as a fundraiser for Samoan Faafafine Organization in Apia, independent Samoa, and for SOFIA the fa`afafine association in Pago Pago, American Samoa.